Posts Tagged “tuition”

The results of the most recent Tuition Discounting Study from the National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO) are telling and worrisome. The study, released last week, examined how much colleges and universities awarded students in scholarship and grants and how deep tuition discounting has become.

The NACUBO study found that the average institutional tuition discount rate for first-time, full-time students hit an estimated 49.1 percent in 2016-2017, up from 48 percent the previous year. The discount rate was highest at small institutions, where the first-time, full-time freshman rate was 50.9 percent for 2016-2017. And perhaps most troubling, more than 25 % of the institutions surveyed have rates well above 50 percent.

Why Does College Tuition Discounting Matter?

Why does this matter?

As Inside Higher Education’s Rick Seltzer points out, the tuition discount rate is defined as institutional grant dollars as a percentage of gross tuition and fee revenue. Translated, a discount rate of 50% means that fifty cents of every tuition dollar never makes it to the college’s bottom line because it is dedicated immediately to financial aid. All but a handful of American colleges and universities are highly dependent on tuition, although they also work to supplement tuition revenue through fundraising in areas like student scholarships.

The problem is that endowments do not fund much institutional grant aid. In 2015-2106, for example, endowments funded only 12.4 percent of institutional grant aid provided to students. In general, 79 percent of aid awarded went to meet need, regardless of whether that need was classified as need-based or merit-based.

Need for Financial Aid Increases but Tuition Revenue is Flat

Mr. Seltzer notes that as tuition prices continue to increase, the share of students with financial need will also likely rise. What’s especially concerning is that the percentage of first-time, full-time freshman receiving institutional grants is estimated to be 87.9 percent in 2016-17. That doesn’t leave much space for the tuition from full-pay students to make much of a dent in the financial aid budget.

The overriding fact is that net tuition revenue per full-time freshman – the cash that supports the college after financial aid — is essentially flat, rising only 0.4 percent in the past year. Worse yet “well over half of survey respondents, 57.7 percent, reported a decline in total undergraduate enrollment between the fall of 2013 and the fall of 2016.” Further, just over half of schools surveyed reported a decrease in enrolled freshmen. The respondents blame price sensitivity, increased competition, and changing demographics as the primary reasons for this decline.

That leaves many colleges in a precarious position. If net tuition revenue is flat, discount rates are rising, the economic headwinds are blowing against them, and their enrollments are declining, financial options are narrowing at most colleges and universities.

A college or university can no longer depend on rising tuition or increased demand to grow its way out of what is now a systemic financial problem.

Discounting Strategies Aren’t Sustainable; Schools Know It but Few Admit It

Yet the most curious result in the survey was on the question of sustainability. In the IHE study, 44 percent of schools reported that their discounting strategies were not sustainable over the long term. Of the remainder, 32 percent said that they were sustainable over the short- but not the long-term. But only 9 percent “were willing to say that their strategies were not sustainable.” They presumably believe that some combination of new programs, better recruitment, and improved marketing strategies could work to improve their competitive position.

Financial aid is a complex question. Many of the colleges now suffering from their discounting practices have increased their discounts, for example, in an effort to serve more financially needy and diverse students. There can be time-specific reasons as well like the development of major new program initiatives.

But the inescapable fact is that American higher education continues to rely on outmoded and archaic financial strategies that used their primary source of revenue – tuition, fees, room and board – to balance out their expenses.

It’s an expense-driven model in which most of the large expenses – financial aid, cost of labor, technology, health care, and debt on capital expenditures – determine the revenue needed, effectively setting the tuition. Any institution increasing tuition much above the cost of inflation, now running at less than two percent, is effectively kicking the can down the road.

Despite the worrisome results of the NACUBO survey, many of us are still betting on American higher education to thrive. It must change how its financial pieces fit together and think imaginatively about how it can finance itself. It is likely that colleges will abandon long-time efforts to finance their capital expenditures exclusively on debt. It is possible to explore creative ways to manage targeted capital campaigns and rethink annual fund efforts. Change will require consortial efforts that move beyond paper and library purchases to see what can be accomplished in common on health care, retirement benefits, and technology.

The NACUBO study forces three conclusions upon us:

- Higher education must evolve more rapidly.

- The broad philosophical debates among staff, trustees, and the faculty must be about institutional sustainability.

- There is only so much time left to take the first big steps.

Everyone knows that money plays a major role in students’ college enrollment decisions. How big a role?

According to a recent study by Royall & Co., the enrollment management and alumni fundraising arm of EAB, “almost one-fifth of students who were admitted to their top choice of college or university in 2016 but decided not to go there turned it down because of the cost of attendance.”

The study’s finding was echoed in my recent conversation with a well-heeled mother of a high school senior, who expressed sentiments I’ve heard repeatedly for more than 20 years. Her daughter wanted to attend an Ivy League institution that had accepted her. The mother preferred that her daughter accept a large merit award to a prestigious research university. It was a simple cost-benefit analysis by parents, who likely would not qualify for financial aid, seeking relief from high tuition sticker prices.

The Royall findings were fairly uniform with different SAT scores and minority groups. Royall’s managing director, Peter Farrell, concludes: “Something has happened more recently that’s accelerated change. It could be demographics. It could be what we’re seeing on the macroeconomic scale about low socioeconomic (status) families being pinched. I don’t know the actual causality of this change in sentiment, but the slope line of concern seems to be upticking.”

When viewed from other perspectives with different data, the conclusions are the same. The fact is that over 40 percent of the first-time college experiences of admitted students are in a community college.

How Colleges Market “Cost of Attendance” Matters

The obvious answer may be that the sticker prices – now approaching $70,000 at a handful of the selective private colleges and universities — are the culprit. In their interpretation, however, Royall argues that families are more fundamentally questioning the value proposition. Royall asserts that colleges must focus on both their marketing and aid strategy. It’s not so much the discount but the marketing and packaging of the cost of attendance.

“Cost of College” Result of Many Factors

The Royall study also highlights other problems in how Americans understand the cost of a college education. Much of the confusion emerges from a variety of factors including how colleges price themselves, what role state and federal aid play in cost of attendance calculations, the differences between need-based and merit financial aid, and the growing importance of merit aid among higher income families.

The consumer and political pressures over the level of indebtedness that stretch back to the days in which some states offered free college tuition further compounds this problem.

New York’s Free Tuition Plan Resonating Across Other States

It is especially relevant today as the progressive agenda in American politics moves forward with new free tuition plans. Governor Cuomo’s program to extend free tuition to New Yorkers whose families make $125,000 or less annually is last week’s dramatic example.

But the New York State approach will likely resonate elsewhere as the progressive wing of the Democratic Party seeks programs and strategies that will re-attach the American middle class by re-aligning the Party’s value proposition to popular middle class entitlements.

It’s gone beyond major policy shifts emerging from polling and anecdotes that have formed the basis of some education policy. The fact is that America has a growing student debt problem set against a backdrop of persistent and historically worsening income inequality.

Free Tuition Plans are Not Without Costs

It may be that free college tuition is a good next move in enlightened federal policy. It’s just that the “all in” costs of added labor, capital, marketing, assessment, and regulatory reporting expenses seem absent from the cost calculation in the program.

It is equally uncertain that free tuition will do anything to build a seamless pathway for students to improve retention and graduation rates.

For families and independent students, it’s all very confusing. Neil Swidey’s feature in the Boston Globe was a sobering assessment of how students did not fully appreciate the ramifications of their grant and loan commitments.

America’s colleges and universities must bear significant responsibility for the confusion students and families face in determining costs and indebtedness. They are hotbeds of cultural inertia, embracing college aid and pricing strategies from the last century that no longer apply, however noble the original intention might have been.

The hard truth is that the pricing of tuition, fees, room and board has broken down. It’s an “all individuals for themselves” approach that conflates and confuses grants and loans without simple definitions and clear direction. It pits one educational institution against another.

It’s a hopeless educational quagmire because the range of state, federal, corporate, donor and college partners all operate under different rules that make it extraordinarily hard to calculate what and whether to save, where to go, and how to know when you have struck the best deal.

It’s time for common sense to win out in tuition pricing strategies. For families, it begins with a better sense of who’s on first base. For tuition-dependent institutions in an uncertain political environment, time is running out.

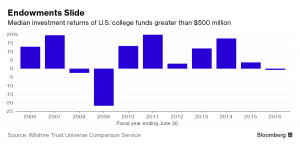

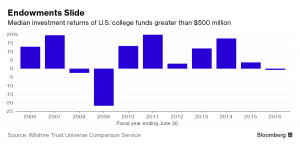

Last week, National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO) and Commonfund released their report on the endowment performance of the 805 colleges and universities who responded to their survey. The outlook was fairly dismal and sheds light on the precarious foundation on which American higher education’s financial model is based.

Endowment Returns Fall to Average Return of -1.9%

According to the report, net return on endowments has continued to decline for the second year, returning on average -1.9% in fiscal 2016. The returns dropped the 10-year average annual returns to 5 percent, down from 6.3 percent in the previous fiscal year. Last year’s average return lowered the five-year average rate to 5.4 percent, down from 9.8 percent a year ago.

Both numbers are lower than the 7.4 percent median annual return that most colleges and universities believe are necessary to maintain their purchasing power – supporting “student financial aid, research, and other vital programs” — over time.

College and University Expenses Increase Even As Endowment Returns Fall

As endowment returns fall, expenses on college and university campuses continue to rise. It is not surprising, therefore, that most respondents reported increasing the money that they spent from their endowments, boosting spending at an average of eight percent which took most colleges above the rate of inflation.

There are a couple of ways to look at this anemic endowment growth. Colleges and universities hold endowments over the long-term. If endowment performance is cyclical, then historical trends suggest that the problem will self-correct over time. The second possibility is more troubling.

The plain facts are that the world has become a less comfortable place with rules and protocols that are uncertain. While some aspects of the market continue to do well, general global and national volatility and growing income inequality – among numerous other factors — may affect the complexity that impacts endowment earnings.

Should the courts decide against lifting the immigration ban, the impact on labor and enrollment in college and university settings alone could be dramatic and disruptive.

Further, most colleges and universities do not have the $34.5 billion in endowment that Harvard enjoys, even when Harvard has also slashed the number of its employees in its endowment office.

Colleges and Universities with Smaller Endowments at Greater Risk

Small institutions are particularly at risk, noted John G. Walda, NACUBO’s president and CEO, in an interview with Inside Higher Ed: “…if we have another couple of years of stagnant returns…they’re going to have to seriously consider cutting back on the amount of dollars that are spent at their institutions….” The question that logically arises is from where will this money come?

Can Schools Make Up Endowment Losses with Debt?

One possibility is that colleges and universities with some level of endowments could borrow to cover lean times, especially to replace depreciated facilities or build new ones. Yet the picture on institutional debt was not particularly encouraging either.

Almost 75 percent of the colleges and universities surveyed carried long-term debt. Among these institutions, the average total debt was $230.2 million as of June 30, 2016, up from $219.1 million in the previous fiscal year. Median debt also rose to $61.5 million from $58.2 million. Two-thirds of those surveyed reported decreasing their overall debt; however, indicating a reluctance to make new investments in areas like infrastructure.

Raising Tuition or Fees is Risky Proposition in Current Climate

Another source of income is, of course, the comprehensive fee that consists of revenue generated by tuition, fees, room and board. Political and consumer voices make large tuition spikes impractical and even dangerous.

It is unlikely that many colleges will package comprehensive fee increases much above the rate of inflation, presuming that they are competently managed institutions. Next year’s tuition numbers will begin to be posted after board meetings over the next few months.

Cold Truth: Higher Ed’s Financial Model is Unsustainable

American higher education must face up to the cold truth that it is operating on an unsustainable financial model, one developed in an era of different demographics, political and consumer concerns, and funding options that originated in the post-Vietnam era of rapid enrollment growth.

The world has changed even if the way that we imagine college and university finances has not.

But there is a more pressing, immediate question for American higher education to address. Some Congressional leaders are working to link endowment spending to student scholarship and debt levels, the danger of which is aptly demonstrated by the fiscal 2016 endowment returns.

Consumers who vote with their feet to reject the historic value proposition of high sticker priced four-year colleges will also affect this brave new world. And the Trump Administration is casting a heightened level of uncertainty with its first actions on immigration and the possible appointment of special groups to look at “higher education reforms.”

We live in interesting times. Now is the time to prepare for them.

It may be an effort to continue Bernie Sander’s legacy by re-introducing the “free college” movement. It may also be a way to recast the Democratic Party in its “return to the working class defender” role. Or, it may be that New York Governor Andrew Cuomo is staking his claim to be one of the new crop of Democratic contenders after the end of the Bush and Clinton American political dynasties.

Whatever the reason, Gov. Cuomo’s proposals on making college affordable and halting student debt will be watched closely.

Gov. Cuomo proposed last week to offer free tuition at New York’s large, comprehensive statewide university systems. Significantly, it would be the first program to expand the free college tuition promise from two to four years. Currently, Tennessee and Oregon have two-year options available.

Cuomo’s plan, called the Excelsior Scholarship, would provide free college tuition at New York’s public two- and four-year institutions to students whose families make up to $125,000 a year. Gov. Cuomo will phase in the program over three years, ending in 2019. It’s meant to provide immediate relief and establish a track record – all before the 2020 campaign.

Students will need to be enrolled full-time to participate in the Excelsior Scholarship. It will also be a “last dollar” strategy after existing state and federal grants have been applied to tuition costs. Cuomo’s office estimated that about 80 percent of New Yorkers make less than $125,000 per annum and about 940,000 of them have college-eligible dependents.

$163 Million Cost is Fraction of New York’s $10+ Billion Higher Ed Budget

The program is projected to cost $163 million annually once the state completes its phase in. New York already has an existing Tuition Assistance Program that provides about $1 billion in support. When capital projects and additional services are factored in, New York spent about $10.7 billion on higher education in 2016.

Governor Cuomo deserves praise as an activist and innovator by offering a potential remedy to rising tuition costs and high levels of student debt. Some critics point out that many lower-income students already qualify for enough aid to cover tuition costs. They note his proposal does not cover the full cost of attendance beyond tuition. Additionally, about one-third of the students attend the CUNY and SUNY systems part-time and would likely not be eligible to participate in the program.

As you might imagine, skeptical Republicans want to look at the cost of this new entitlement program.

In a sense, it’s a little like the opening salvos on the Affordable Care Act. Like access to health care, there is strong public support to address college debt. The federal government has already invested billions in grants and loans extended to millions of Americans through popular existing programs like the Pell grant.

Set against this national backdrop, New York represents an excellent test case. With two huge state university systems in place as the foundation of a comprehensive higher education platform, New York is also the home to the country’s largest collection of private colleges and universities. Many of these private colleges serve their local communities admitting predominantly New York State residents. They share the same admissions market with their public neighbors.

What Impact Will Excelsior Scholarship Have on Private Colleges?

The first and most obvious question is what will happen to New York when its statewide admissions recruiting is thrown into chaos and disarray when Mr. Cuomo’s proposal disproportionately tilts the scales toward public sector institutions?

Since the less well-endowed private colleges are heavily tuition dependent, what impact will the migration of large numbers of students to public colleges and universities have on the viability and durability of local private institutions?

It is unreasonable to assume that increasing the college going rates will have a net neutral effect on the size of private college admission classes after the state government intervenes to price out private colleges from the competition for incoming students.

Can New York’s Public Higher Ed Handle Influx of Students?

Further, can the community college and upper division public college and university systems handle the projected influx of students given their current faculty and staff levels, programmatic base, and facilities infrastructure? Is it fair to have the state government expect them to do so? If not, what is the real “all in” cost of Mr. Cuomo’s proposal?

Third, does the admission of larger numbers into the public sector pipeline translate into worsening persistence and graduation rates as the numbers are not matched by corresponding spending increases, including in counseling and support services that are critical to making expanding public sector opportunities viable? There is considerable danger in having government argue in complex higher education communities like New York that government-aligned institutions like CUNY and SUNY can be redeployed to solve problems like student debt and the college-going rate. Let me be clear here. They are part of the solution and their funding should reflect their enormous value to their localities, regions, and the state.

The history of New York suggests that the best solution is a thoughtful collaborative one that values education where it happens. The economic vitality of the state going forward will depend on it.

On September 13, a House Ways & Means Subcommittee will hold a hearing that, according to Janet Lorin in Bloomberg, “is set to look at how colleges, through their tax exempt endowments, are trying to reduce tuition.” Ms. Lorin reports that the subcommittee hearing will feature testimony from policy experts and college officials.

It’s an interesting time to examine college endowments. As Ms. Lorin reports, most endowments are expected to post investment declines for fiscal 2016.

The House Ways & Means Subcommittee on Oversight will also look at how endowments intersect with the tax-exempt status enjoyed by colleges and universities. As Lauren Aronson, a spokeswoman for the House Ways and Means Committee, relates: “This is another step that the committee is taking to understand what colleges are doing to address soaring college costs through their endowments and nonprofit-tax status.”

The committee’s hearing is separate from its joint inquiry with the Senate Finance Committee, whose members requested data in areas such as endowment spending, fees paid to investment managers, and rules on naming rights for donors from the 56 wealthiest private colleges last February.

For argument’s sake, let’s not take a position on whether this is information gathering or a Congressional witch hunt fueled by consumer polling. We can all agree that the effort to provide debt relief to Americans is a good idea.

It’s not so much the noble aspiration but the approach that should raise eyebrows. Words and actions are always important. How you do it – and how you convey your intent – matters even more in these settings.

Most Colleges Have Little or No Endowments

Let’s get real, Congress, and establish the facts:

- The 56 wealthiest private universities do not reflect the rest of American higher education, not even remotely. They are large research complexes scaled and identified by purpose as distinct and different from undergraduate colleges, teaching universities, and community colleges.

- Most colleges have little or no endowments, are heavily tuition-dependent, and are in deep debt for capital improvements. Many are, effectively, open admissions institutions with escalating tuition discounts.

- Tax exemption is a broader issue than its relationship with endowments. The federal government granted tax exemption because colleges and universities serve a public good. They still do.

- Tax exemption assists private colleges especially because it bridges the gap between public and private colleges, with public colleges also receiving additional state subsidies. It essentially levels some of the playing field among institutions in a decentralized higher education system.

- State support over the past 20 years has decreased for public colleges and universities, with many now re-characterizing themselves not as state-assisted but as “state located” because of shrinking government support.

- Congress must be certain to review government support across all programs for colleges and universities, whether public or private, as part of its fact-finding effort. Is it possible that the decline in government support has contributed to rising tuition sticker prices? Is the government really blameless in this debt crisis?

- How many federal regulations affect colleges and universities? Is it likely that the cost of these reporting requirements also jacks up tuition substantially? Most colleges and universities are almost entirely dependent on tuition revenue, yet are encumbered by across-the-board government reporting mandates, regardless of their size.

- For those colleges with endowments that actually contribute to their bottom line, the rule on spending is often something like a draw down of 5% on a trailing 12-quarter average. When endowments drop due to market conditions, is it really feasible for Congress to deny them the flexibility to manage prudently in bad times over the long term?

American Higher Education is Not Monolithic

It is a fundamental mistake to paint American higher education as though similar conditions apply across the broad diversity of institutions that comprise it. What would be helpful is for Congress to assume less and learn more before it holds its hearings, given the idiosyncratic nature of the information it recently requested.

To do so, Congressional hearings must begin with the right questions. And they might do so by approaching higher education not as an arrogant, bloated industry in need of “big stick” political discipline.

There’s plenty of blame to go around for high tuition sticker prices. It’s time to make the pillars of federal policy more clear rather than creating artificial linkages among endowments, tax exemption, and tuition as a popular if insufficient explanation of why college costs so much.