Posts Tagged “endowments”

One of the great myths about American higher education is that all colleges are wealthy. If most Americans have an mental image of a college, it’s often a bucolic bricks-and-mortar residential facility separated by rolling green lawns, entered through an impressive if forbidding-looking gate, and populated by attractive students who drive fancy cars.

One of the great myths about American higher education is that all colleges are wealthy. If most Americans have an mental image of a college, it’s often a bucolic bricks-and-mortar residential facility separated by rolling green lawns, entered through an impressive if forbidding-looking gate, and populated by attractive students who drive fancy cars.

What they can’t see past the stately columns or newest facility highlighted by energetic tour guides is the level of deferred campus maintenance. They fail to comprehend the amount of debt or the inability for a college to sustain its existing campus footprint. They don’t see is that the average discount – the percentage of total gross tuition and fee revenue institutions give back to students as grant-based financial aid – is now 50 cents on the dollar at most colleges. And they seldom appreciate how reasonable staff and faculty compensation, including health and retiree benefits, the impact of technology, and the rising cost of government regulations and reports constrain most college operating and capital budgets.

On one level, a college is a business. But at the same time, it’s a heavily regulated business that produces – in business terms – a product that requires significant inputs of labor, capital, and technology.

College Revenue Streams Are Drying Up

The problem is that college and university sources of revenue are drying up. Consumers are voting with their feet as over half choose public- or locally-supported options like community colleges, for-profit providers, or certificate programs. The sticker price that “sticks” in the minds of these consumers is the widely-reported $70,000 annual price tag at the most selective colleges and universities.

At most colleges, it’s no longer possible to match revenue to expenses by setting tuition prices to meet annual operating needs.

College Endowments Are Not Magical Money Trees

But what about tapping into the endowment? In the minds of consumers and many public officials, an endowment is a kind of imaginary money tree from which additional needs are met.

The reality is that few colleges or universities have large enough endowments to produce significant revenue. In 2015, the National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO) and the Common Fund reported that the 94 institutions with endowments of $1 billion or higher control 75 percent of all endowments nationwide. If colleges typically draw down five percent on a rolling quarterly average, the amount available to most of the remaining 3,900 institutions surveyed is negligible at best.

The other potential sources of revenue are auxiliary services, like residential housing or athletics, or debt. Revenue from auxiliary services are essentially flat, with many colleges using residential housing to support their academic programs. Only one in eight colleges have sports programs that break even. And debt – often used indiscriminately and for the wrong reasons – is a particularly worrisome source of support. Many colleges are at the end of their debt capacity or find the amount capped by trustee action.

Fundraising Campaigns Aren’t Financial Panaceas

What is left is revenue from fundraising. Colleges will sometimes tie a presidential search to the reputation of prospective candidates as potential fundraisers. But the cold facts are that there may only be about 50 colleges and universities in America where fundraising is anything more than running in place.

The problem is that fundraising has become seen as a panacea to cure all ills that plays out like every college is a major research university with a significant, mature fundraising machine in place. To create momentum and garner visibility, most colleges favor a comprehensive campaign. Under this approach, colleges throw almost everything into the mix, including their annual fund, deferred gifts, and any specially cultivated donations. The college establishes targeted goals in specific categories. The president makes periodic reports at campaign events. The college offers updated reports within a specified time frame about how well the institution is doing to reach its stated goal.

Campaigns are expensive, and at times, counterproductive to the immediate goals that a college needs to meet. To assess the success of a comprehensive campaign, multiply the “all in” amount raised annually before the campaign started by the number of years of the campaign. When this number is subtracted from the announced comprehensive campaign goal, how much is needed to reach the announced campaign goal?

Does it really make sense for colleges to play like the big boys when what they are actually doing is re-characterizing money that they are already raising without the costs associated with a full-fledged campaign?

Targeted, Micro Campaigns are Alternatives to Comprehensive Campaigns

For colleges and universities that do not have the money, staff, and alumni and donor base to run a full-scale, multi-year comprehensive campaign, there may be better, more targeted approach. These institutions should consider putting most of their work into cultivating – that is, growing — the annual fund and deferred gifts.

To the extent that a college seeks the optics of a successful campaign, its leadership should think about micro-campaigns that address specific, identified, and fundable campus needs. College stakeholders can touch and feel these advances. The effect is the same, absent the bragging rights to an inflated comprehensive campaign goal.

One size – or approach – does not fit every college. Success in fundraising relies upon common sense and a clear understanding of what’s possible given the scale and resources available.

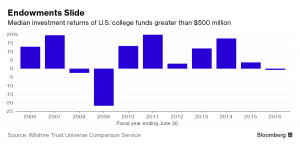

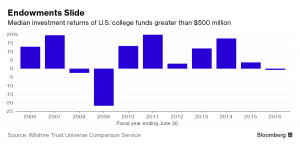

Last week, National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO) and Commonfund released their report on the endowment performance of the 805 colleges and universities who responded to their survey. The outlook was fairly dismal and sheds light on the precarious foundation on which American higher education’s financial model is based.

Endowment Returns Fall to Average Return of -1.9%

According to the report, net return on endowments has continued to decline for the second year, returning on average -1.9% in fiscal 2016. The returns dropped the 10-year average annual returns to 5 percent, down from 6.3 percent in the previous fiscal year. Last year’s average return lowered the five-year average rate to 5.4 percent, down from 9.8 percent a year ago.

Both numbers are lower than the 7.4 percent median annual return that most colleges and universities believe are necessary to maintain their purchasing power – supporting “student financial aid, research, and other vital programs” — over time.

College and University Expenses Increase Even As Endowment Returns Fall

As endowment returns fall, expenses on college and university campuses continue to rise. It is not surprising, therefore, that most respondents reported increasing the money that they spent from their endowments, boosting spending at an average of eight percent which took most colleges above the rate of inflation.

There are a couple of ways to look at this anemic endowment growth. Colleges and universities hold endowments over the long-term. If endowment performance is cyclical, then historical trends suggest that the problem will self-correct over time. The second possibility is more troubling.

The plain facts are that the world has become a less comfortable place with rules and protocols that are uncertain. While some aspects of the market continue to do well, general global and national volatility and growing income inequality – among numerous other factors — may affect the complexity that impacts endowment earnings.

Should the courts decide against lifting the immigration ban, the impact on labor and enrollment in college and university settings alone could be dramatic and disruptive.

Further, most colleges and universities do not have the $34.5 billion in endowment that Harvard enjoys, even when Harvard has also slashed the number of its employees in its endowment office.

Colleges and Universities with Smaller Endowments at Greater Risk

Small institutions are particularly at risk, noted John G. Walda, NACUBO’s president and CEO, in an interview with Inside Higher Ed: “…if we have another couple of years of stagnant returns…they’re going to have to seriously consider cutting back on the amount of dollars that are spent at their institutions….” The question that logically arises is from where will this money come?

Can Schools Make Up Endowment Losses with Debt?

One possibility is that colleges and universities with some level of endowments could borrow to cover lean times, especially to replace depreciated facilities or build new ones. Yet the picture on institutional debt was not particularly encouraging either.

Almost 75 percent of the colleges and universities surveyed carried long-term debt. Among these institutions, the average total debt was $230.2 million as of June 30, 2016, up from $219.1 million in the previous fiscal year. Median debt also rose to $61.5 million from $58.2 million. Two-thirds of those surveyed reported decreasing their overall debt; however, indicating a reluctance to make new investments in areas like infrastructure.

Raising Tuition or Fees is Risky Proposition in Current Climate

Another source of income is, of course, the comprehensive fee that consists of revenue generated by tuition, fees, room and board. Political and consumer voices make large tuition spikes impractical and even dangerous.

It is unlikely that many colleges will package comprehensive fee increases much above the rate of inflation, presuming that they are competently managed institutions. Next year’s tuition numbers will begin to be posted after board meetings over the next few months.

Cold Truth: Higher Ed’s Financial Model is Unsustainable

American higher education must face up to the cold truth that it is operating on an unsustainable financial model, one developed in an era of different demographics, political and consumer concerns, and funding options that originated in the post-Vietnam era of rapid enrollment growth.

The world has changed even if the way that we imagine college and university finances has not.

But there is a more pressing, immediate question for American higher education to address. Some Congressional leaders are working to link endowment spending to student scholarship and debt levels, the danger of which is aptly demonstrated by the fiscal 2016 endowment returns.

Consumers who vote with their feet to reject the historic value proposition of high sticker priced four-year colleges will also affect this brave new world. And the Trump Administration is casting a heightened level of uncertainty with its first actions on immigration and the possible appointment of special groups to look at “higher education reforms.”

We live in interesting times. Now is the time to prepare for them.

One of the striking features of the new presidential administration appears to be the difference between fact and perception. On most levels, it seems that optics matter more than words. It also seems that facts are an afterthought to the positions floated. Further, it looks like many positions shift regularly depending upon how the outcome is likely to play with the American public.

It’s not that outcomes don’t matter; in fact, they do. But words also matter in the end. And facts inform the words that are spoken. Facts are the foundation that opens the dialogue, builds the trust, and sets a policy on which interested parties can agree. Facts aren’t subjective and they can’t be taken too literally. Facts are just facts.

For the moment, those of us who think and write about higher education can’t be certain about what’s coming.

While President-elect Trump has named a Secretary of Education, there’s not really enough to go on yet to forecast an education strategy.

What will be the policies of the Trump Administration? Will they reflect traditional priorities established by Congressional Republicans? Are there likely to be new Executive Branch initiatives?

Is the combination of national higher education associations, policy institutes and think tanks, and campus-based higher education leadership part of the swamp that Mr. Trump promised to drain or are they a resource to which he can turn as an outsider seeking informed opinions?

President-elect Trump has a right to claim some time to set up his shop. We’ll know more soon. We can withhold our powder and wish him well until perceptions become proposals. But it’s a short grace period when the issues are so pressing, consumer dissatisfaction is increasing, and pre-election campaign positions potentially threaten how colleges operate.

Colleges are a microcosm of American society. Almost every action taken will have some effect on them. It’s important to watch and learn.

It is even more critical for state and federal legislators to understand how colleges work and the pressures that they face. The facts always matter.

A recent example demonstrates the danger of creating a quagmire in the so-called “Washington swamp.” US Representative Tom Reed (R-Corning, NY) has reported that he is confronting the college cost crisis and the student loan debt issue through a variety of proposals that he will sponsor and support.

For Congressman Reed, the effort is personal: “I have firsthand experience with this myself having $110,000 worth of student loan debt when I completed my studies . . . Now, with my own daughter being a freshman at the University of Buffalo, this is something I have dealt with personally.”

Congressman Reed is justified to worry about high college tuition sticker prices and rising student debt. He supports the expansion of the Perkins Loan Program and Pell grants, for example, to help families deal with these costs. But many of his proposals suggest that he is not especially well versed about higher education issues that go well beyond legitimate questions about high sticker prices before tuition discounts and where comprehensive student debt originates.

Most troubling are two proposals grouped under what Mr. Reed has developed as a “Vision for Students” platform. The proposed federal legislation has the unfortunate and pejorative title of “Reducing Excessive Debt and Unfair Costs of Education Act.” In this bill, Mr. Reed targets about 90 institutions that have over $1 billion in endowment funds. His proposal would mandate that these endowment funds reduce a student’s tuition by 25 percent. This mandate might be expanded to other institutions as well.

If these colleges and universities failed to provide tuition relief, they would become subject to hefty tax penalties. Further, Rep. Reed’s proposal would require college campuses to submit plans to keep their costs below the rate of inflation. Colleges that failed to comply could lose federal aid.

Let’s set aside the issue of why the federal government that fails to keep its own expenses below the rate of inflation, suffers from growing consumer discontent, and has not modernized its own infrastructure should pick out sectors of the American economy – in this case higher education – for special regulatory treatment.

Instead, let’s look at the facts. There is no particular reason that $1 billion should be a cap for Rep. Reed’s proposals. Colleges and universities differ by purpose, scale in size and operations, and student income levels. A $1 billion cap is meaningless.

Further, endowments are often a collection of donor-restricted funds and not an unrestricted pot of gold that colleges use as discretionary accounts.

Finally, a five percent drawdown annually on a rolling twelve-quarter average will not generate the revenue necessary to support a 25% cut in tuition at most institutions.

In addition, colleges and universities that raise tuition – or allow their tuition discounts to rise beyond the level where net tuition revenue no longer increases – will either adjust to marketplace dynamics, merge, or close. It’s one of those pesky inescapable facts that should guide progressive federal policy.

Higher education is a little like the patient who will not improve if the wrong medicine is prescribed. As a start, it might be better to sit down with higher education’s leadership to ask how higher education works, what efficiencies can be created, and how the state and federal governments can be helpful and knowledgeable partners in a shared need to ensure an educated workforce.

On September 13, a House Ways & Means Subcommittee will hold a hearing that, according to Janet Lorin in Bloomberg, “is set to look at how colleges, through their tax exempt endowments, are trying to reduce tuition.” Ms. Lorin reports that the subcommittee hearing will feature testimony from policy experts and college officials.

It’s an interesting time to examine college endowments. As Ms. Lorin reports, most endowments are expected to post investment declines for fiscal 2016.

The House Ways & Means Subcommittee on Oversight will also look at how endowments intersect with the tax-exempt status enjoyed by colleges and universities. As Lauren Aronson, a spokeswoman for the House Ways and Means Committee, relates: “This is another step that the committee is taking to understand what colleges are doing to address soaring college costs through their endowments and nonprofit-tax status.”

The committee’s hearing is separate from its joint inquiry with the Senate Finance Committee, whose members requested data in areas such as endowment spending, fees paid to investment managers, and rules on naming rights for donors from the 56 wealthiest private colleges last February.

For argument’s sake, let’s not take a position on whether this is information gathering or a Congressional witch hunt fueled by consumer polling. We can all agree that the effort to provide debt relief to Americans is a good idea.

It’s not so much the noble aspiration but the approach that should raise eyebrows. Words and actions are always important. How you do it – and how you convey your intent – matters even more in these settings.

Most Colleges Have Little or No Endowments

Let’s get real, Congress, and establish the facts:

- The 56 wealthiest private universities do not reflect the rest of American higher education, not even remotely. They are large research complexes scaled and identified by purpose as distinct and different from undergraduate colleges, teaching universities, and community colleges.

- Most colleges have little or no endowments, are heavily tuition-dependent, and are in deep debt for capital improvements. Many are, effectively, open admissions institutions with escalating tuition discounts.

- Tax exemption is a broader issue than its relationship with endowments. The federal government granted tax exemption because colleges and universities serve a public good. They still do.

- Tax exemption assists private colleges especially because it bridges the gap between public and private colleges, with public colleges also receiving additional state subsidies. It essentially levels some of the playing field among institutions in a decentralized higher education system.

- State support over the past 20 years has decreased for public colleges and universities, with many now re-characterizing themselves not as state-assisted but as “state located” because of shrinking government support.

- Congress must be certain to review government support across all programs for colleges and universities, whether public or private, as part of its fact-finding effort. Is it possible that the decline in government support has contributed to rising tuition sticker prices? Is the government really blameless in this debt crisis?

- How many federal regulations affect colleges and universities? Is it likely that the cost of these reporting requirements also jacks up tuition substantially? Most colleges and universities are almost entirely dependent on tuition revenue, yet are encumbered by across-the-board government reporting mandates, regardless of their size.

- For those colleges with endowments that actually contribute to their bottom line, the rule on spending is often something like a draw down of 5% on a trailing 12-quarter average. When endowments drop due to market conditions, is it really feasible for Congress to deny them the flexibility to manage prudently in bad times over the long term?

American Higher Education is Not Monolithic

It is a fundamental mistake to paint American higher education as though similar conditions apply across the broad diversity of institutions that comprise it. What would be helpful is for Congress to assume less and learn more before it holds its hearings, given the idiosyncratic nature of the information it recently requested.

To do so, Congressional hearings must begin with the right questions. And they might do so by approaching higher education not as an arrogant, bloated industry in need of “big stick” political discipline.

There’s plenty of blame to go around for high tuition sticker prices. It’s time to make the pillars of federal policy more clear rather than creating artificial linkages among endowments, tax exemption, and tuition as a popular if insufficient explanation of why college costs so much.

One of the great myths about American higher education is that all colleges are wealthy. If most Americans have an mental image of a college, it’s often a bucolic bricks-and-mortar residential facility separated by rolling green lawns, entered through an impressive if forbidding-looking gate, and populated by attractive students who drive fancy cars.

One of the great myths about American higher education is that all colleges are wealthy. If most Americans have an mental image of a college, it’s often a bucolic bricks-and-mortar residential facility separated by rolling green lawns, entered through an impressive if forbidding-looking gate, and populated by attractive students who drive fancy cars.