In Higher Education Policy, Facts Matter

One of the striking features of the new presidential administration appears to be the difference between fact and perception. On most levels, it seems that optics matter more than words. It also seems that facts are an afterthought to the positions floated. Further, it looks like many positions shift regularly depending upon how the outcome is likely to play with the American public.

It’s not that outcomes don’t matter; in fact, they do. But words also matter in the end. And facts inform the words that are spoken. Facts are the foundation that opens the dialogue, builds the trust, and sets a policy on which interested parties can agree. Facts aren’t subjective and they can’t be taken too literally. Facts are just facts.

For the moment, those of us who think and write about higher education can’t be certain about what’s coming.

While President-elect Trump has named a Secretary of Education, there’s not really enough to go on yet to forecast an education strategy.

What will be the policies of the Trump Administration? Will they reflect traditional priorities established by Congressional Republicans? Are there likely to be new Executive Branch initiatives?

Is the combination of national higher education associations, policy institutes and think tanks, and campus-based higher education leadership part of the swamp that Mr. Trump promised to drain or are they a resource to which he can turn as an outsider seeking informed opinions?

President-elect Trump has a right to claim some time to set up his shop. We’ll know more soon. We can withhold our powder and wish him well until perceptions become proposals. But it’s a short grace period when the issues are so pressing, consumer dissatisfaction is increasing, and pre-election campaign positions potentially threaten how colleges operate.

Colleges are a microcosm of American society. Almost every action taken will have some effect on them. It’s important to watch and learn.

It is even more critical for state and federal legislators to understand how colleges work and the pressures that they face. The facts always matter.

A recent example demonstrates the danger of creating a quagmire in the so-called “Washington swamp.” US Representative Tom Reed (R-Corning, NY) has reported that he is confronting the college cost crisis and the student loan debt issue through a variety of proposals that he will sponsor and support.

For Congressman Reed, the effort is personal: “I have firsthand experience with this myself having $110,000 worth of student loan debt when I completed my studies . . . Now, with my own daughter being a freshman at the University of Buffalo, this is something I have dealt with personally.”

Congressman Reed is justified to worry about high college tuition sticker prices and rising student debt. He supports the expansion of the Perkins Loan Program and Pell grants, for example, to help families deal with these costs. But many of his proposals suggest that he is not especially well versed about higher education issues that go well beyond legitimate questions about high sticker prices before tuition discounts and where comprehensive student debt originates.

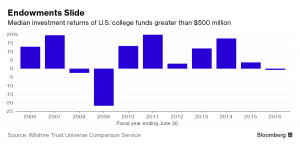

Most troubling are two proposals grouped under what Mr. Reed has developed as a “Vision for Students” platform. The proposed federal legislation has the unfortunate and pejorative title of “Reducing Excessive Debt and Unfair Costs of Education Act.” In this bill, Mr. Reed targets about 90 institutions that have over $1 billion in endowment funds. His proposal would mandate that these endowment funds reduce a student’s tuition by 25 percent. This mandate might be expanded to other institutions as well.

If these colleges and universities failed to provide tuition relief, they would become subject to hefty tax penalties. Further, Rep. Reed’s proposal would require college campuses to submit plans to keep their costs below the rate of inflation. Colleges that failed to comply could lose federal aid.

Let’s set aside the issue of why the federal government that fails to keep its own expenses below the rate of inflation, suffers from growing consumer discontent, and has not modernized its own infrastructure should pick out sectors of the American economy – in this case higher education – for special regulatory treatment.

Instead, let’s look at the facts. There is no particular reason that $1 billion should be a cap for Rep. Reed’s proposals. Colleges and universities differ by purpose, scale in size and operations, and student income levels. A $1 billion cap is meaningless.

Further, endowments are often a collection of donor-restricted funds and not an unrestricted pot of gold that colleges use as discretionary accounts.

Finally, a five percent drawdown annually on a rolling twelve-quarter average will not generate the revenue necessary to support a 25% cut in tuition at most institutions.

In addition, colleges and universities that raise tuition – or allow their tuition discounts to rise beyond the level where net tuition revenue no longer increases – will either adjust to marketplace dynamics, merge, or close. It’s one of those pesky inescapable facts that should guide progressive federal policy.

Higher education is a little like the patient who will not improve if the wrong medicine is prescribed. As a start, it might be better to sit down with higher education’s leadership to ask how higher education works, what efficiencies can be created, and how the state and federal governments can be helpful and knowledgeable partners in a shared need to ensure an educated workforce.