Posts Tagged “Inside Higher Education”

Inside Higher Education just released its annual “Survey of College and University Presidents.” The results, which cover a wide variety of topics, are revealing if not surprising. There are too many individual findings to discuss in a single article; therefore, we’ll concentrate on the findings that deal most directly with the state of higher education as an industry and the health and sustainability of its institutions.

College Presidents Worried About Finances & Public Perception

Collectively, the survey findings suggest that college presidents are worried about higher education’s fiscal health, deteriorating public perceptions of American higher education, and enrollment stabilization and growth, especially at tuition-dependent institutions.

One of the most striking aspects is that the survey did not reveal wide swings in college and university perceptions on these issues compared to previous years. The levels of concern remain high, likely indicating that these issues continue to be deeply troubling to leaders, but no single issue rose to the top. That having been said, the survey responses forecast continued uncertainty about the future of higher education.

Presidents Expect Higher Education Mergers, Closings to Continue

Inside Higher Education (IHE) measured fiscal health in part by asking presidents about institutional mergers, closures, and acquisitions. They found, “About a third of the presidents agree that more than ten colleges or universities will close or merge in the next year, while another forty percent say at least five colleges will do so.”

A striking finding is that nearly 12 percent of college presidents “predict that their own institution could fold or combine in the next five years.”

Concern over mergers and closures relates directly to the financial health of the various sectors of higher education. On this issue, the results stabilized when compared to the wide swings of previous years. But there were differences across institutional sectors (e.g. public, private, community colleges, flagship, regional).

Private College Presidents More Confident of Their Own Sustainability

Private college presidents are the most confident in the viability of their institutions over the next decade. There was renewed hope, especially among private four-year college leaders, in the ability of their own institutions to be sufficiently nimble and adaptable to be sustainable going forward, an encouraging sign from previous pessimistic assessments.

One especially interesting finding questioned which sector was believed to have the most sustainable business model. The presidents identified wealthy elite private colleges and universities and public flagship universities as the best able to withstand uncertainty.

Interestingly, the numbers dropped off dramatically for the other sectors. As IHE noted, “Community colleges followed at 44 percent, with other public institutions (25 percent), private colleges (11 percent) and for-profit institutions (9 percent) lagging.”

Apparently, survey respondents did not share the confidence of private sector presidents, for instance, when judging the sustainability of small, private colleges as a sector.

Leaders Believe Public Perception of Higher Ed Based on Misunderstanding

In response to survey questions about the public perceptions of American higher education, “[p]residents overwhelmingly believe the public’s skepticism is based on misunderstandings about colleges’ wealth, how much they charge (and spend) and the overall purpose of higher education.”

The survey respondents believe that the public has been swayed by misperceptions about them. IHE noted: “Asked to assess which of several factors were the most responsible for declining public support, 98 percent of the presidents cited ‘concerns about college affordability and student debt’.” Other factors identified were the greater need for career preparation for students, perceptions of liberal political bias, and, to a much lesser extent, an under-representation of low-income students.

Higher Education has an Optics Problem But Leaders Hesitant to Speak Out

These responses imply fairly strongly that American higher education has an optics problem. It continues to play defense rather than move forward on several fronts with an aggressive response to perceived misconceptions. In part, it comes down to higher education leaders’ — such as the presidents surveyed — capacity and willingness to speak out.

IHE reported: “Asked whether they had responded to the turbulent political movement in 2017 by speaking out more on political issues, 55 percent said yes and 45 percent said no.” There was also little sense of introspection on whether there was much truth to negative public perceptions.

Meeting Enrollment Goals is Concern for College Presidents

Finally, there continues to be a high level of concern among college and university presidents about their ability to meet enrollment projections. IHE noted: “eighty-two percent of presidents described themselves as either ‘very’ (42 percent) or ‘somewhat concerned’ (40 percent) about meeting their institution’s ‘target number of undergraduates’.” These numbers were down from previous years.

In this year’s survey, presidents worried about retaining students and finding enough full-pay students to subsidize institutional financial aid.

Inside Higher Education’s survey remains a valuable annual “pulse check” for higher education. The results this year suggest that, while the concerns remain the same, college presidents often perceive that the clouds are more ominous over the other types of institutions and for higher education generally.

There is an open question about how contemplative and self-reflective higher education is about itself. And there is clearly concern about how politics and public perception affect higher education policy and overall sustainability. The cumulative effect of the survey results suggests that higher education is in a period of steady transition.

Community colleges are the entry point to higher education for millions of Americans, but, according to Inside Higher Education’s 2017 Survey of Community College Presidents, their leaders report significant enrollment challenges and precarious financial support.

Six in 10 of the 236 community college presidents reported a decline in enrollment over the past three years. Their response often was to add new programs, increase strategies to support student transfers, grow their marketing budgets, add new online programs, and freeze or cut tuition. Significantly, most looked first to program enhancements designed to boost enrollment rather than cuts to cover deficits and meet expenses.

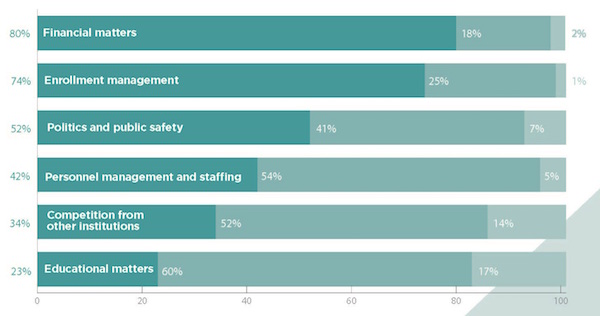

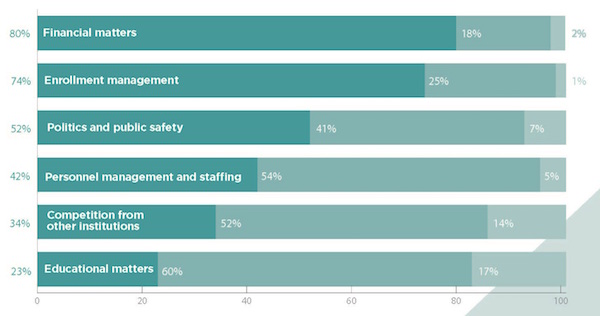

Community college presidents report financial matters and enrollment management are top concerns.

The enrollment and financial difficulties faced by community college leaders reflect broader trends. Employment opportunities have increased with the improving economy, for example, causing some enrollment declines. Further, the tactics utilized to stabilize community college finances often reflect the approaches adopted elsewhere among four-year, graduate, and professional schools.

Community Colleges Often First Entry to Higher Education

But what’s most telling is that a uniform communications and marketing message has not yet taken hold to build a case for community colleges.

The plain fact is that community colleges are the defining point of access for most students in the American higher education system.

Well over forty percent of American college students have some educational experience in a community college. For most of these, it is their first college experience.

If community colleges provide primary access in a world of shifting demographics, persistent income inequality, and the failing college and business and financial models that are causing open consumer revolt over sticker prices, should enlightened local, state and federal policies reward community colleges more deliberately for the public good that they provide?

Isn’t it time for policymakers to set basic parameters in place to offer an agenda that sponsors access and better supports the institutions like community colleges which provide it?

Higher Education is Lifelong Learning Experience

For policymakers to make a difference, they must first see what educational consumers already understand – education is a life-long learning experience “from cradle through career” and beyond — that creates a pathway along which citizens travel.

Education remains the great safety valve in American society, assimilating new immigrant groups and providing Americans in general with their best hope to secure a sustainable place in the American middle class.

But the pathway goes beyond access. Getting students into the educational pipeline, as free tuition plans in states like New York and Rhode Island propose to do, is not enough. The likely effect will be to jam the pipeline and blame the students or the institutions when retention and graduation rates do not improve.

Regardless of how the financial pieces are put together, community colleges must have reliable sources of revenue to do their jobs, ensuring that accepted students not only attend but persist and graduate in reasonable time.

A realistic community college operating model is not likely to suggest that they be like four-year colleges, offering a full range of residential and non-academic programming. There is a good case for public/private partnerships in areas like housing, dining, and wellness facilities, however, to support students who need basic services. But any new money that flows into community colleges must assist students to move along the education pathway at reasonable cost.

Community colleges are different from residential four-year institutions. It’s part of the secret to their success. It’s also one important reason why they remain more affordable than most other types of postsecondary education.

In the future, it’s essential to better position community colleges within higher education where internal infighting often erupts over questions of process and prestige. Community colleges are not junior colleges nor are they four-year wannabe institutions. They are the primary access point for most Americans seeking to live out the American dream.

For policymakers, it’s time to take a step back to avoid the pitfalls and costs of populist strategies, band-aid solutions, and knee-jerk, reactive panaceas.

Changes in American higher education must be systemic and systematic. It begins by understanding higher education, how it works, and how and why the pieces fit together.

American higher education institutions must change their operating models, which are now built too heavily on tuition and government aid. Determining new pricing strategies requires imagination and new thinking, but it does not absolve local, state, and federal governments from some measure of continuing support.

Since GI Bill, Higher Education is a Right

American society decided with the GI Bill after World War II that education was a right and not a privilege. In the minds of most Americans, this debate is over.

It’s time to understand instead that a successful and robust higher education system — one that includes community colleges — must be decentralized and well funded to be a continuing safety value.

Education grows the middle class, supports a well-educated citizenry, and develops an employable workforce. It’s not a solution built on incremental funding increases that don’t address, access, choice, persistence, graduation rates, and employability.

But it is an urgent question. How do you build and fund a life-long education pathway that best serves American citizens?

Higher education is misunderstood and struggling financially, but the majority of college and university presidents are increasingly confident that their institutions are financially stable. These seemingly contradictions were found in Inside Higher Education’s annual survey of 706 campus leaders.

Let’s set aside the obvious political concerns among presidents about the Trump Administration or the selection of the new U.S. Education Secretary that underscored many of the questions put to the presidents in the IHE survey, which was conducted in January and early February.

It’s really too soon to tell what the new policies will be toward higher education or what rollbacks of disliked Obama Administration programs and dictates are likely to occur. President Trump has paid scant attention to higher education during the election, the transition, and the first months of his tenure.

The higher education community will have a lot to say as positions and platforms become clearer. But these comments should be seasoned and informed after the fact and not anticipate the best hopes or worst fears before the first steps occur.

The findings that address the climate facing American higher education are the most fascinating.

Disconnect Between Academe and Much of American Society

Perhaps the most interesting finding is that the “2016 election exposed a disconnect between academe and much of American society.” Seventy percent of the presidents sense a growing level of anti-intellectualism in American life. Two-thirds of the presidents agreed that campus protests created optics that the American public interpreted as unfriendly to conservative views.

The presidents were especially concerned that the current political climate works against consensus views on science, including but not limited to areas like climate change.

A majority of the presidents agreed that higher education suffered badly in public perceptions, including in areas like campus diversity and inclusion. They believed that campus racial unrest “led many prospective students and families to think colleges are less welcoming of diverse populations than is really the case.”

Campus Leaders Frustrated with Media Focus on Wealthy, Elite Schools

These concerns extend to the heart of the higher education enterprise. Eighty-four percent believe, for example, that media attention to the rising levels of student debt makes a college education seem less affordable than it actually is. These presidents are also frustrated by the media obsession with a few institutions with large endowments that paints all colleges as wealthy when in fact most of them are not. The majority of presidents also agree that the construction of Taj Mahal-like facilities in rising competitive consumer wars contributes to these perceptions.

In addition, the presidents were concerned about the attitudinal gulf between their concentration on students as individuals who graduate as educated citizens and the “graduates as workforce” focus of most of American society.

Alison Kadlek, senior vice president and director of higher education and workforce engagement in higher education at Public Agenda, notes in the IHE survey release: “What we’re hearing is that the tight connection between education and socioeconomic mobility has been weakened for the public, and confidence in college as a certain path to economic security is waning….”

In other areas, there were signs of improving perceptions. Public college and university presidents were increasingly confident, for example, in the financial stability of their institutions. But among the uncertainties and anxieties faced, the one dominant feature remains a weakening public perception of American higher education.

Leaders Have Not Made Strong Enough Case for Value of Higher Education

One lesson seems obvious from the IHE’s survey. American higher education is not building a case that is sufficient – or, more troubling, even compelling — for the role it plays in American society.

Higher education leadership has failed to capture the narrative succinctly to explain the value proposition to American families and their children, politicians, business leaders, and the wider public.

The belief in the bedrock principle that higher education is the best path into the middle class seems increasingly at risk.

Leadership carries with it considerable risk. But if America’s colleges and universities lose control of their own narrative, they subject themselves to a broad-brush analysis that no longer resonates with key stakeholders, like the American families upon whom they depend for tuition and other means of support. Higher education also runs the risk of being painted less than comprehensively, defined instead by one issue or perception rather than the whole of its parts.

In a sense, the best solution is to violate the principle that all politics is local by thinking about how to craft perceptions beyond the college gates.

While it is heartening to articulate a series of high road value statements about the lasting importance of a college education that will always ring true, the message must also account for the realities that colleges and universities face in the 21st century.

In today’s climate, it may be as critical to stress how colleges and universities transform lives, meet workforce needs, and shape the development of American society as to rely on older arguments about educated citizens.

The goal is the same. It’s just that the language needs to be re-imagined and re-stated more clearly.