Posts Tagged “community colleges”

Community colleges are the entry point to higher education for millions of Americans, but, according to Inside Higher Education’s 2017 Survey of Community College Presidents, their leaders report significant enrollment challenges and precarious financial support.

Six in 10 of the 236 community college presidents reported a decline in enrollment over the past three years. Their response often was to add new programs, increase strategies to support student transfers, grow their marketing budgets, add new online programs, and freeze or cut tuition. Significantly, most looked first to program enhancements designed to boost enrollment rather than cuts to cover deficits and meet expenses.

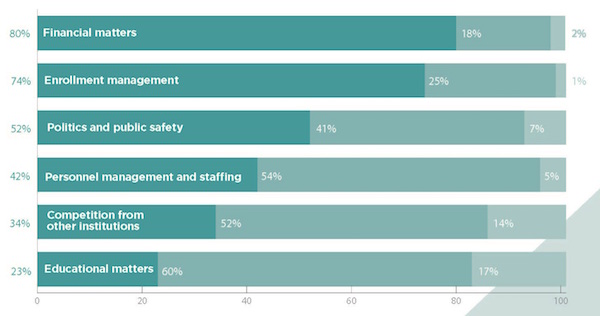

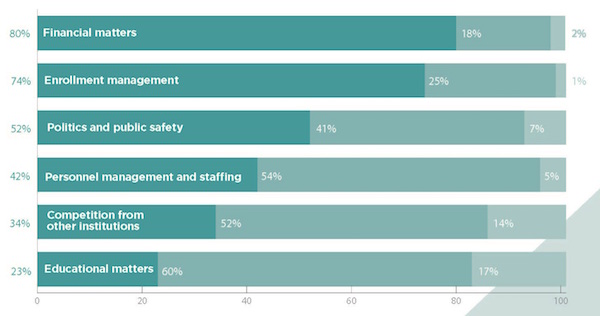

Community college presidents report financial matters and enrollment management are top concerns.

The enrollment and financial difficulties faced by community college leaders reflect broader trends. Employment opportunities have increased with the improving economy, for example, causing some enrollment declines. Further, the tactics utilized to stabilize community college finances often reflect the approaches adopted elsewhere among four-year, graduate, and professional schools.

Community Colleges Often First Entry to Higher Education

But what’s most telling is that a uniform communications and marketing message has not yet taken hold to build a case for community colleges.

The plain fact is that community colleges are the defining point of access for most students in the American higher education system.

Well over forty percent of American college students have some educational experience in a community college. For most of these, it is their first college experience.

If community colleges provide primary access in a world of shifting demographics, persistent income inequality, and the failing college and business and financial models that are causing open consumer revolt over sticker prices, should enlightened local, state and federal policies reward community colleges more deliberately for the public good that they provide?

Isn’t it time for policymakers to set basic parameters in place to offer an agenda that sponsors access and better supports the institutions like community colleges which provide it?

Higher Education is Lifelong Learning Experience

For policymakers to make a difference, they must first see what educational consumers already understand – education is a life-long learning experience “from cradle through career” and beyond — that creates a pathway along which citizens travel.

Education remains the great safety valve in American society, assimilating new immigrant groups and providing Americans in general with their best hope to secure a sustainable place in the American middle class.

But the pathway goes beyond access. Getting students into the educational pipeline, as free tuition plans in states like New York and Rhode Island propose to do, is not enough. The likely effect will be to jam the pipeline and blame the students or the institutions when retention and graduation rates do not improve.

Regardless of how the financial pieces are put together, community colleges must have reliable sources of revenue to do their jobs, ensuring that accepted students not only attend but persist and graduate in reasonable time.

A realistic community college operating model is not likely to suggest that they be like four-year colleges, offering a full range of residential and non-academic programming. There is a good case for public/private partnerships in areas like housing, dining, and wellness facilities, however, to support students who need basic services. But any new money that flows into community colleges must assist students to move along the education pathway at reasonable cost.

Community colleges are different from residential four-year institutions. It’s part of the secret to their success. It’s also one important reason why they remain more affordable than most other types of postsecondary education.

In the future, it’s essential to better position community colleges within higher education where internal infighting often erupts over questions of process and prestige. Community colleges are not junior colleges nor are they four-year wannabe institutions. They are the primary access point for most Americans seeking to live out the American dream.

For policymakers, it’s time to take a step back to avoid the pitfalls and costs of populist strategies, band-aid solutions, and knee-jerk, reactive panaceas.

Changes in American higher education must be systemic and systematic. It begins by understanding higher education, how it works, and how and why the pieces fit together.

American higher education institutions must change their operating models, which are now built too heavily on tuition and government aid. Determining new pricing strategies requires imagination and new thinking, but it does not absolve local, state, and federal governments from some measure of continuing support.

Since GI Bill, Higher Education is a Right

American society decided with the GI Bill after World War II that education was a right and not a privilege. In the minds of most Americans, this debate is over.

It’s time to understand instead that a successful and robust higher education system — one that includes community colleges — must be decentralized and well funded to be a continuing safety value.

Education grows the middle class, supports a well-educated citizenry, and develops an employable workforce. It’s not a solution built on incremental funding increases that don’t address, access, choice, persistence, graduation rates, and employability.

But it is an urgent question. How do you build and fund a life-long education pathway that best serves American citizens?

Reporting in last week’s Inside Higher Education, Kasia Kovacs reviewed the findings of the Commission on the Future of Higher Education, an initiative of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, funded by the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Dr. Michael McPherson, co-chair of the commission and a well-respected economist, former college president, and president of the Spencer Foundation, spoke to Ms. Kovacs about the Commission’s report, A Primer on the College Student Journey, which used data to form conclusions about the state of undergraduate education at two- and four-year colleges.

Dr. Michael McPherson, co-chair of the commission and a well-respected economist, former college president, and president of the Spencer Foundation, spoke to Ms. Kovacs about the Commission’s report, A Primer on the College Student Journey, which used data to form conclusions about the state of undergraduate education at two- and four-year colleges.

Dr. McPherson reported: “Our ambition is to help the American population, the American people, to appreciate what a college education means now in the United States, which is something much broader and more complex than what a number of us might have thought a few years ago.” Dr. McPherson and his colleagues interpreted data from a wide range of sources, including the National Center for Education Statistics.

The Commission’s findings are critical to our understanding of what’s happening in American higher education, providing a snapshot of who goes to college, how they pay for it, what happens when they get there, how they fare, and what directional changes they make.

The findings present a complex and compelling story about opportunities and challenges facing higher education, with the balance tilted toward an optimistic and hopeful view overall. Some of the more interesting findings are:

- Gender and ethnicity and race matter. In 2015, 50 percent of 25-29 year old women had a college degree compared with 41 percent of men. Almost three-fourths of Asian students 25-29 years held at least an associates degree. This number drops to 54 percent for white students, 31 percent for black students, and 27 percent for Hispanic students in the same category.

- Half of America’s high school graduates need remedial assistance in college, and that help often falls short. Only 28 percent of students in remedial classes at two-year colleges actually earned a degree in 8.5 years.

- Students are borrowing more. In 2000, 50 percent of students took out loans, with the number increasing ten percentage points by 2012. Only nine percent defaulted on their loans, but this number rose to 24 percent if they did not graduate. Ms. Kovacs reported that the Commission found that “borrowers at greatest risk of defaulting are typically those who take out the smallest loan amounts.”

- Transfer students follow what the Commission calls a “multi-directional transfer swirl.” Almost one-third of students transferred or were simultaneously enrolled in two institutions over six years. A surprising number were lateral transfers; 15 percent of two-year students transferred to another two-year college and 17.2 percent of students at four-year colleges switched to two-year institutions.

The Commission’s findings suggest implications for American higher education. These implications will powerfully affect the level of workforce preparation, any potential improvement to the disparity in income and social inequality, and in time, America’s commitment to higher education as a kind of safety value “great equalizer.”

The first implication is that a complex mix of familial, social, cultural, economic, and psychological factors affect whether a high school graduate seeks a college degree. It may be that matching application pools to demographic changes backed by renewed commitments to increased financial aid is not enough to provide the twin goals of a well-educated citizenry and an educated workforce.

Is it also possible that the levels of debt already in place now, fostering a consumer revolt over college costs and presidential positions on free tuition and ameliorating middle class debt, may actually discourage college attendance? In pledging relief, is there a corresponding compelling argument on why a debt-laden college degree is so critical to many Americans?

For some high school graduates and their families, there is not a good answer on why they should spend the money. The optics can shape the perception dramatically.

A second implication is that the stark data on college preparedness suggests that there is a growing dissonance between what basic education teaches and what higher education expects of its students. College faculty regularly complain about the lack of student preparation as they engage newly admitted students. Has the conversation between basic and higher education leadership – one that goes beyond the politicizing of issues like test scores at the state and federal level – occurred on how to develop a common set of expectations that make the handoff between these groups more seamless and successful?

And finally, the Commission’s findings speak volumes about what choices students make within the higher education system. The process of transferring within a “multidirectional transfer swirl” is hardly seamless. The failure to increase qualified counseling, provide safety nets, and better general directional advice can be as big a deterrent as college costs in dampening higher graduation rates, at both the two- and four-year levels.

Higher education is the cornerstone upon which America’s successful participation in the competitive global economy rests. It’s likely an uneven evolution ahead. The Carnegie Corporation study helps because it allows us to get our facts straight first.

Tim Goral published an extremely interesting interview with former president of the Appalachian College Association, Alice Brown, in University Business last month.

Ms. Brown’s comments reflected the wisdom of a professional who had served for 15 years leading a consortium of 35 private, liberal arts colleges in North Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia and West Virginia. Her remarks were wide-ranging but one set in particular stood out above the rest. Ms. Brown claimed that “the central Appalachian region has a unique character – the students have different needs and different goals.”

Ms. Brown explained that students in her college consortium “come from a different culture.” She suggested that “the culture is very family oriented . . It’s a culture that doesn’t give kids a lot of experiences in the outside world. They come from a closed culture and they can continue to get that at a small college.”

Ms. Brown argued that this need reinforced the value proposition for small, rural liberal arts colleges that provide a nurturing climate crafted to encourage student success. These colleges did so on terms acceptable to the cultural and social environment into which these students were born and to which they hope to return.

The dominance of family, social, psychological and cultural forces on a student’s decision to attend and remain at college should not be underestimated.

Higher education leadership at two- and four-year colleges in Massachusetts have conveyed to me separately and repeatedly the same story.For many of their students, success means something different than the stereotypical views of hyper-competitive students angling for admission to Princeton before accepting a seat in a future admissions class at Yale Law.

For many American students, their ambition is not dramatically different than among the most competitive students in any admissions class. The best and brightest students can come from anywhere. But the differences can be magnified when shaped by geography, the ability to handle debt, the need to support themselves and others, and the reasons for seeking a college degree. It’s often more pragmatic than broadening.

As one group of community college counselors reported in a conversation with me about how best to create a seamless transfer pathway, it’s often impossible for a Boston–born student to imagine success beyond a transfer to the local four-year public, U-Mass/Boston. There’s nothing wrong with this ambition, especially given the amazing work undertaken at the University. But the failure – if there is one – is in the narrowness in how the transfer student approaches the goal of a four-year degree.

The counselors reported that it goes well beyond finances to include the practicality and insularity that comes with tribal ties to family, neighborhood, culture and region, whether rural or urban.

UMass is logical because it has a good educational program at a stop on the MBTA subway line. It makes sense to a student whose mindset reflects the familial and cultural values that inform their decision and reinforce their sense of self that may extend only as far as the end of the subway.

This raises an interesting policy question.

If the purpose of American higher education is broader than workforce training, what values, if any, does this education support? Should colleges and universities enforce the cultural and social norms of their region – or at least their market draw – or should they teach to the broader values in American society? Is the purpose of American higher education principally to create global citizens?

Are critics of colleges and universities who “coddle” their students with elaborate safety nets in a nurturing environment really missing the point when the very success of student service programs is measured by metrics upon which accreditors, state and federal regulators, consumers, parents, students and graduates judge them?

If a student feels alienated from the mainstream campus culture, the isolation typically conveyed by many first-time freshman as “homesickness” can have a dramatic impact in areas like retention. Yet we know that graduation rates are highest when American colleges and universities match their educational program with student service support and employment after graduation. It makes the value proposition clear to students and their families.

It may be that residence life programs must serve two masters. The first is to be certain that college shapes, defines and supports a constantly evolving understanding of American values in a global society across its academic and residence life programs. But it may also be true that to do so colleges and universities must better understand the competing claims tugging at students drawn from the splendid parochialism of their upbringing.

For many of us, there seems to be a growing chasm between the coarse, vulgar individualism of polarized, partisan political behavior in American society and the best values shaped by its imperfect Founders. Colleges and universities have a critical role to play in setting the stage to better align social, familial and cultural values to the more endearing traditions in American society before we muck them up any further.